Hate Speech Adds New Weapons to Armed Conflict

By NETWORK MEDIA GROUP (NMG)

Friday, December 28, 2018

HSIPAW, Shan State, Myanmar – The sounds of gunshots and heavy shelling are far from new for the residents of this village in Myanmar’s northern Shan State, near the border with China. But what is new for them is a type of warfare that is no less lethal online battles that are pitting their ethnic communities against each other in a country struggling to gain an elusive peace.

For the villagers here, as well as in neighboring Kyaukme, Namtu and Lashio townships, the familiar sounds of war are a signal to flee to monasteries and churches.

But is not as easy to flee from the online conflict, where social media has become a battleground for continuing warfare among Myanmar’s different ethnic groups, and actors that freely use and come across hate speech and threats of violence.

This is so in the case of two communities, the Shan and Ta-ang, which are from just two of Myanmar’s at least 135 ethnic groups. Ethnic armies from these two groups, the Restoration Council for Shan State (RCSS) and the Ta-ang National Liberation Army (TNLA), have been fighting in northern Shan state.

They used to live harmoniously, but have become divided after their ethnic armies were split in their responses to the Myanmar government’s efforts at a peace dialogue. In the more open political atmosphere since the country’s transition from military rule, social media became a space for animosity among ethnic groups to thrive, adding a difficult aspect to the armed conflict already underway between RCSS and TNLA.

The Shan Women Action Network (SWAN) is a Shan women’s organization working for displaced Shan women and children since 1999. Nang Hein is director of SWAN.

“People changed because of fighting. After armed conflicts, we have seen communal tensions. We are really concerned about this. These should not be there. Actually, these fightings are not related to communal conflict. RCSS is Restoration Council of Shan State. TNLA is Ta-ang National Liberation Army. It is between them, and not related to people. But, many people are writing hate speeches on social media, and the hatred between two communities intensified.” Nang Hein (director) Shan Women Action Network (SWAN)

Facebook discussions relating to the two communities are rife with swear words. Users put angry, insulting comments in discussion threads around pages such as Tai Freedom, the Facebook page run by the RCSS, as well as the TNLA’s social media accounts for news.

Facebook accounts with Shan names cuss and swear against Ta-ang people and Ta-ang leaders and accounts with Ta-ang names do the same to to Shan people and their leaders.

A common arena of online warfare among clashing communities is the comment sections under the news posts of news organizations, such as the Shan Herald Agency for News or the Network Media Group, which cover issues in Shan State. Angry posts such as “kill that Shan leader” or “f-ck that Ta-ang leader” are not uncommon.

The reposting of fake news, disinformation, tampered photos, or plain wrong information further amplifies tensions that have already been getting worse in northern Shan state.

Against the backdrop of Myanmar’s political change since 2011, hostility in northern Shan state has picked as communities feel freer to define and express their ethnic roots. People of different ethnic groups here used to have and use Burman names, but more have been changing to Shan and Ta-ang names.

It also became easier to identify who was who – Shan names usually start with “Sai” and Ta-ang ones, with “Mai”.

“If they see names with “Sai” or names with “Mai” online, they yell at each other. ‘Who are you? The area you live in is not your area. It is ours.’ They are blaming each other. These are very bad. ‘If I met you anywhere, I will kill you,’ they said. ‘We Shan people should kill all Ta-ang. We Ta-ang should kill all Shans.’ But, who knows? “Sai” could be “Mai” and “Mai” could be “Sai”. These “Sai” and “Mai” could also be not “Sai” or “Mai”, could be other people.” Mai San Yet (Secretary General, Ta-ang Students and Youth Organization)

An incident in late September 2018 shows how the circulation of fake news poisons the already tense atmosphere among the Ta-ang and Shan groups, including their armies. The TNLA had arrested a Shan woman from Muse, Nang Mokham, whom it accused of having reported to government soldiers the presence of two TNLA soldiers. After these two came to her shop to collect taxes, they figured in a shootout with government troops; one died and the other was injured.

Soon after, fake news raced across social media saying that Nang Mokham e had been killed while in detention by the TNLA. Some Shan communities in Namkham believed this, adding to the hostility between the Shan and the Ta-ang.. However, this was untrue, and Nang Mohkam was freed after other ethnic groups lobbied the TNLA to release her.

Sai Muang is chief editor of Shan Herald Agency for News (SHAN). It has branch offices in Chiang Mai, Thailand,Taunggi and Lashio in northern Shan State, publishing and broadcasting online in Shan, Burmese and English. These days, Sai Muang and his editorial staff make extra efforts to verify information and sources in order to avoid being victimized by false information that would exacerbate tension between the Shan and Ta-ang communities.

“Before 2015, fighting were between TNLA and government troops. (The) only difficulty for us was to contact Military officers. They usually don’t answer our calls. But now, let’s say if someone is killed, the TNLA killed or RCSS killed, we need to be very careful not to create hate speech. More and more incidents like killings, more and more difficult for us to cover.” Sai Muang (chief editor) The Shan Herald Agency for News (SHAN)

The fighting between the Shan and the Ta-ang, also called Palaung, is one example of how armed conflict has escalated between those that signed a peace agreement with the Myanmar government, and those that did not. RCSS is among 10 ethic armies that have, since 2015, signed a National Ceasefire Agreement while Myanmar undertakes a peace dialogue to end decades of internal conflict. The TNLA has not.

That ceasefire agreement has not brought more, or lasting, peace. In fact, since 2015, it has changed the characteristic of fighting in northern Shan State. In the past, most fighting had occurred between government troops and ethnic armies. These days, fighting is underway between those ethnic armed groups that are party to the ceasefire and those that are not.

The tensions between the RCSS and TNLA increased after the Shan army RCSS, based on Thai-Burma border moved, some of its troops to the northern areas of Shan State. This created problems about control of some areas with another Shan army based in the north, the Shan State Progressive Party, as well as the TNLA.

Against this landscape of conflict, Mai Naing Naing Oo, chief editor of the Mar Naga Ta-ang news group based in Lashio, says these are tricky times for journalists and professional media in general.

Some local news groups typically use ethnic descriptions, whether Ta-ang or Shan, in their names. But some mistakenly think this means they represent their ethnic armies. Sai Muang, SHAN editor, agrees that these misperceptions pose a big challenge to the news organization’s work. It is the same with other ethnic news organizations.

“What happened was people don’t trust us. The problem and fighting were between RCSS and TNLA. When we are reporting about human rights abuses relating to RCSS or TNLA, they mistrust us. For example, our SHAN is based in Chiang Mai so they believe we have relation with RCSS. So, TNLA don’t want to talk to us. As our name is Shan Herald, we have “SHAN” in our name. People think we will be biased for Shan. If we interview SSPP, RCSS thinks these guy are working for SSPP. When we cover RCSS, SSPP thinks this group based on border and they might be the same with RCSS. In these mistrusts, it is very difficult for us to work. We need to be very careful.” Sai Muang (chief editor) The Shan Herald Agency for News (SHAN)

The RCSS and TNLA routinely trade accusations in the conflict – in both the information and military fronts – between them.

Maj. Mai Aik Kyaw, spokesman for the TNLA, explains his army’s views about RCSS.

“RCSS uses their propaganda machine as a weapon. When there is fighting, they create something in one or two communities to misunderstand us by using fake news or untrue stories. Or they make problem in communities. As they create news to misunderstand us or misunderstand between two communities, people had to flee. RCSS also create mistrust between the communities.” Maj.Mai Aik Kyaw (Spokesman) TNLA

Lt Col Sai Muang speaks for RCSS.

“More and more fighting means we have more mistrust and misunderstanding. On the other hand, they (TNLA and SSPP) think we have an advantage on NCA, and that we are trying to expand the areas under control. Actually, it is not true, because we have talked about this many times. There have been our troops in northern areas since 2006. There are misunderstandings on this issue. On the other hand, we also doubt (think?) that they have done more attacks on us as these areas are on business routes.” Lt. Col. Sai Muang (RCSS/SSA)

As the number of armed groups in northern Shan State has grown over the years, so has the fear among villagers in or around the areas of Hispaw, Kyaukme, Namtu, Namkham and Lashio townships.

“Two kinds of fighting occured in this November. First one is with Burmese Army. Another is with RCSS. We sometimes join with SSPP to fight against RCSS. There have been 4 armed clashes with the Burmese Army this month. There were more than 10 clashes with RCSS, both big and small fighting.” Maj. Mai Aik Kyaw, spokesperson of TNLA.

Before 2015, some 200,000 people had already been displaced by the fighting between government troops and ethnic armies and human rights abuses in northern Shan State, as well as Kachin State, according to the UN High Commissioner for Refugees.

More war refugees in recent years have been added to already displaced population. From 2017 to September 2018, more than 68,000 people fled the fighting in Shan State, the United Nations Office for Coordination of Humanitarian Affairs said in an Oct. 8 update.

For some displaced villagers, it was their third time to flee home. For others, it was their fourth.

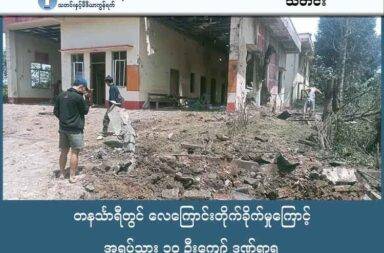

Combined troops from the TNLA and SSPP clashed with RCSS soldiers on Nov. 23 in Nar Lort village here in Hsipaw Township.

“I came here as there was heavy fighting. There were 3-4 times like this before. This time serious fighting and we have to run. (I don’t want) fighting anymore. We had to flee many times. We cannot work well. Some elders had fled 4 or 5 times. We fled, stayed here about a week and we went back to village if the situation was ok. Some were shot. Now, there are two villagers at hospital with gunshot wounds. We are afraid. We send our mothers and children first. We followed later.” Daw Thet Thet Khine (War Refugee) Hsipaw.

The whole village of Pan Long in Namtu township, which is Thet Thet Khine’s hometown, had to flee to Hsipaw’s Boedaw Monastery. Residents say they do not know when they could go back. No one can guarantee their safety.

“Frankly speaking, now there is no group protecting civilians and there is no safety for people. People living in those areas, including Shan and Ta-ang people, are suffering from fighting. Whatever armed group comes, they have to feed them. They are afraid of who comes to them. There was shooting even into the monasteries. One famous monk was killed. Even monks don’t dare to stay at the monasteries during Lent.” Sai Muang (Editor, SHAN)

Locals say villagers have been arrested and are still detained on suspicion of having links to armed groups.

Mai San Yet is secretary general of the Ta-ang Students and Youth Organization. He works in a campaign to reduce illiteracy among Ta-ang children, apart from being involved in efforts to bridge the Ta-ang and Shan communities.

“Especially young people, both male and female – they were accused by Burmese military for connection with TNLA or SSPP or unlawful organization. People were arrested without any evidence. Some were arrested by the army and given to the police. Seems they are creating cases against civilians. This is a challenge for young people.” Mai Sar Yet (Secretary General, Ta-ang Students and Youth Organization)

Mai San Yet says that locals who are found with sticks, knives, ropes and farming materials are accused of having connections with ethnic armed groups such as TNLA, the Kachin Independence Organization (KIO) or the SSPP.

“They accuse people as they like. And people are arrested. If it’s only arrest, there will not be a big problem. But as soon as villagers were arrested, they were beaten. Some were beaten until dead.” Mai Sar Yet (Secretary General, Ta-ang Students and Youth Organization)

In a November interview, Mai Sar Yet discussed what he said were unexplained disappearances of young people, Shan as well as Ta-ang.

“There are more than 40 people who disappeared in our Ta-ang community. Some people know where they are and who arrested them. But nobody dared speak out. Some came to us and said ‘We don’t dare to speak out because some groups told us if you act as witness, your life will not be guaranteed. So, we don’t dare to come. We don’t dare to speak out’. We could not find some people. We don’t know where are they and what happened to them. There were more than twenty people who were forcibly disappeared only in Namtu township. We could not trace them.” Mai Sar Yet (Secretary General, Ta-ang Students and Youth Organization)

Dr. Chayan Vadhanaphuti is the director of Regional Center for Social Science and Sustainable Development, Chiang Mai University, in Thailand. He is also an expert and analyst on Burma.

“Who is benefiting from the conflicts? It is important to know who is benefiting from creating mistrust between different ethnic communities, creating this hatred, rather than who is controlling (this) from behind.” Dr. Chayan Vadhanaphuti

Rebuilding the trust among the Shan and Ta-ang – especially given the open and abundant use of disinformation and hate speech as weapons of online warfare – will take a lot of work.

“Generally, Ta-ang people support the Ta-ang army. Among Shan people, some support RCSS and some support SSPP. So, there is a split in the Shan community itself. But people should be careful not to have hatred as different communities support different ethnic armies. The conflict between two organizations can be solved. But it would take time to resolve the conflict between ethnic communities.” Maung Maung Soe (expert on ethnic issues and political analyst)

This Story was published/produced through a grant received for the Southeast Asian Press Alliance SEAPA(seapa.org) 2018-2019 Journalism Fellowship Program, supported by a grant from the Office of the United Nations High Commissioner for Human Rights (OHCHR). The views expressed do not reflect the official opinion of OHCHR.